Binoculars

Binoculars, field glasses or binocular telescopes are a pair of identical or mirror-symmetrical telescopes mounted side-by-side and aligned to point accurately in the same direction, allowing the viewer to use both eyes (binocular vision) when viewing distant objects. Most are sized to be held using both hands, although sizes vary widely from opera glasses to large pedestal mounted military models. Many different abbreviations are used for binoculars, including glasses, nocs, noculars, binos and bins.

Unlike a (monocular) telescope, binoculars give users a three-dimensional image: for nearer objects the two views, presented to each of the viewer's eyes from slightly different viewpoints, produce a merged view with an impression of depth.

Contents |

Optical designs

Galilean binoculars

Almost from the invention of the telescope in the 17th century the advantages of mounting two of them side by side for binocular vision seems to have been explored.[1] Most early binoculars used Galilean optics; that is they used a convex objective and a concave eyepiece lens. The Galilean design has the advantage of presenting an erect image but has a narrow field of view and is not capable of very high magnification. This type of construction is still used in very cheap models and in opera glasses or theater glasses.

Prism binoculars

An improved image and higher magnification can be achieved in a construction binoculars employing Keplerian optics, where the image formed by the objective lens is viewed through a positive eyepiece lens (ocular). This configuration has the disadvantage that the image is inverted. There are different ways of correcting these disadvantages.

Porro prism binoculars are named after Italian optician Ignazio Porro who patented this image erecting system in 1854 and later refined by makers like the Carl Zeiss company in the 1890s.[1] Binoculars of this type use a Porro prism in a double prism Z-shaped configuration to erect the image. This feature results in binoculars that are wide, with objective lenses that are well separated but offset from the eyepieces. Porro prism designs have the added benefit of folding the optical path so that the physical length of the binoculars is less than the focal length of the objective and wider spacing of the objectives gives a better sensation of depth.Thus, the size of binoculars are reduced.

Binoculars using roof prisms may have appeared as early as the 1870s in a design by Achille Victor Emile Daubresse.[2][3] Most roof prism binoculars use either the Abbe-Koenig prism (named after Ernst Karl Abbe and Albert Koenig and patented by Carl Zeiss in 1905) or Schmidt-Pechan prism (invented in 1899) designs to erect the image and fold the optical path. They have objective lenses that are approximately in line with the eyepieces.

Roof-prisms designs create an instrument that is narrower and more compact than Porro prisms. There is also a difference in image brightness. Porro-prism binoculars will inherently produce a brighter image than roof-prism binoculars of the same magnification, objective size, and optical quality, because the roof-prism design employs silvered surfaces that reduce light transmission by 12% to 15%. Roof-prisms designs also require tighter tolerances as far as alignment of their optical elements (collimation). This adds to their expense since the design requires them to use fixed elements that need to be set at a high degree of collimation at the factory. Porro prisms binoculars occasionally need their prism sets to be re-aligned to bring them into collimation. The fixed alignment in roof-prism designs means the binoculars normally won't need re-collimation.[4]

Optical parameters

Binoculars are usually designed for the specific application for which they are intended. Those different designs create certain optical parameters (some of which may be listed on the prism cover plate of the binocular). Those parameters are:

- Magnification: The ratio of the focal length of the eyepiece divided into the focal length of the objective gives the linear magnifying power of binoculars (sometimes expressed as "diameters"). A magnification of factor 7, for example, produces an image as if one were 7 times closer to the object. The amount of magnification depends upon the application the binoculars are designed for. Hand-held binoculars have lower magnifications so they will be less susceptible to shaking. A larger magnification leads to a smaller field of view.

- Objective diameter: The diameter of the objective lens determines how much light can be gathered to form an image. This number directly affects performance. When magnification and quality is equal, the larger the second binocular number, the brighter the image as well as the sharper the image. An 8×40, then, will produce a brighter and sharper image than an 8×25, even though both enlarge the image an identical eight times. The larger front lenses in the 8×40 also produce wider beams of light (exit pupil) that leave the eyepieces. This makes it more comfortable to view with an 8×40 than an 8×25. It is usually expressed in millimeters. It is customary to categorize binoculars by the magnification × the objective diameter; e.g. 7×50.

- Field of view: The field of view of a pair of binoculars is determined by its optical design. It is usually notated in a linear value, such as how many feet (meters) in width will be seen at 1,000 yards (or 1,000 m), or in an angular value of how many degrees can be viewed.

- Exit pupil: Binoculars concentrate the light gathered by the objective into a beam, the exit pupil, whose diameter is the objective diameter divided by the magnifying power. For maximum effective light-gathering and brightest image, the exit pupil should equal the diameter of the fully dilated iris of the human eye— about 7 mm, reducing with age. If the cone of light streaming out of the binoculars is larger than the pupil it is going into, any light larger than the pupil is wasted in terms of providing information to the eye. In daytime use the human pupil is typically dilated about 3 mm, which is about the exit pupil of a 7×21 binocular. Much larger 7×50 binoculars will produce a cone of light bigger than the pupil it is entering, and this light will, in the day, be wasted. It is therefore seemingly pointless to carry around a larger instrument. However, a larger exit pupil makes it easier to put the eye where it can receive the light: anywhere in the large exit pupil cone of light will do. This ease of placement helps avoid vignetting, which is a darkened or obscured view that occurs when the light path is partially blocked. And, it means that the image can be quickly found which is important when looking at birds or game animals that move rapidly, or by a seaman on the deck of a pitching boat. Narrow exit pupil binoculars may also be fatiguing because the instrument must be held exactly in place in front of the eyes to provide a useful image. Finally, many people use their binoculars at dusk, in overcast conditions, and at night, when their pupils are larger. Thus the daytime exit pupil is not a universally desirable standard. For comfort, ease of use, and flexibility in applications, larger binoculars with larger exit pupils are satisfying choices even if their capability is not fully used by day.

- Eye relief: Eye relief is the distance from the rear eyepiece lens to the exit pupil or eye point.[5] It is the distance the observer must position his or her eye behind the eyepiece in order to see an unvignetted image. The longer the focal length of the eyepiece, the greater the eye relief. Binoculars may have eye relief ranging from a few millimeters to 2.5 centimeters or more. Eye relief can be particularly important for eyeglass wearers. The eye of an eyeglass wearer is typically further from the eye piece which necessitates a longer eye relief in order to still see the entire field of view. Binoculars with short eye relief can also be hard to use in instances where it is difficult to hold them steady.

- Close focus distance: Close focus distance is the closest point that the binocular can focus on. This distance varies from about 0.5m to 30m, depending upon the design of the binoculars.

Mechanical design

Focus and adjustment

Binoculars have a focusing arrangement which changes the distance between ocular and objective lenses. Normally there are two different arrangements used to provide focus, "independent focus" and "central focusing":

- Independent focus is an arrangement where the two telescopes are focused independently by adjusting each eyepiece. Binoculars designed for heavy field use, such as military applications, traditionally have used independent focusing.

- Central focusing is an arrangement which involves rotation of a central focusing wheel to adjust both tubes together. In addition, one of the two eyepieces can be further adjusted to compensate for differences between the viewer's eyes (usually by rotating the eyepiece in its mount). Because the focal change effected by the adjustable eyepiece can be measured in the customary unit of refractive power, the diopter, the adjustable eyepiece itself is often called a "diopter". Once this adjustment has been made for a given viewer, the binoculars can be refocused on an object at a different distance by using the focusing wheel to move both tubes together without eyepiece readjustment.

There are "focus-free" or "fixed-focus" binoculars that have no focusing mechanism. They are designed to have a fixed depth of field from a relatively close distance to infinity, having a large hyperfocal distance. These are considered to be compromise designs, suited for convenience, but not well suited for work that falls outside their designed range.[6]

Some binoculars have adjustable magnification, zoom binoculars, intended to give the user the flexibility of having a single pair of binoculars with a wide range of magnifications, usually by moving a "zoom" lever. This is accomplished by a complex series of adjusting lenses similar to a zoom camera lens. These designs are noted to be a compromise and even a gimmick[7] since they add bulk, complexity and fragility to the binocular. The complex optical path also leads to a narrow field of view and a large drop in brightness at high zoom.[8] Models also have to match the magnification for both eyes throughout the zoom range and hold collimation to avoid eye strain and fatigue.[9]

Most modern binoculars are also adjustable via a hinged construction that enables the distance between the two telescope halves to be adjusted to accommodate viewers with different eye separation or "interpupillary distance". Most are optimized for the interpupillary distance (typically 56mm) for adults.[10]

Image stability

Some binoculars use image-stabilization technology to reduce shake at higher magnifications. This is done by having a gyroscope move part of the instrument, or by powered mechanisms driven by gyroscopic or inertial detectors, or via a mount designed to oppose and damp the effect of shaking movements. Stabilization may be enabled or disabled by the user as required. These techniques allow binoculars up to 20× to be hand-held, and much improve the image stability of lower-power instruments. There are some disadvantages: the image may not be quite as good as the best unstabilized binoculars when tripod-mounted, stabilized binoculars also tend to be more expensive and heavier than similarly specified non-stabilised binoculars.

Alignment

The two telescopes in binoculars are aligned in parallel (collimated), to produce a single circular, apparently three-dimensional, image. Misalignment will cause the binoculars to produce a double image. Even slight misalignment will cause vague discomfort and visual fatigue as the brain tries to combine the skewed images.[11]

Alignment is preformed by small movements to the prisms, by adjusting an internal support cell or by turning external set screws, or by adjusting the position of the objective via eccentric rings built into the objective cell. Alignment is usually done by a professional, although the externally mounted adjustment features can be accessed by the end user.

Optical coatings

Since a typical binocular has 6 to 10 optical elements [12] with special characteristics and up to 16 air-to-glass surfaces, binocular manufactures use different types of optical coatings for technical reasons and to improve the image they produce.

Anti-reflective coatings

Anti-reflective coatings reduce light lost at every optical surface through reflection at each surface. Reducing reflection via anti-reflective coatings also reduces the amount of "lost" light bouncing around inside the binocular which can making the image appear hazy (low contrast). A pair of binoculars with good optical coatings may yield a brighter image than uncoated binoculars with a larger objective lens, on account of superior light transmission through the assembly. A classic lens-coating material is magnesium fluoride, which reduces reflected light from 5% to 1%. Modern lens coatings consist of complex multi-layers and reflect only 0.25% or less to yield an image with maximum brightness and natural colors.

The brighter that a lens appear when looking at its coatings, the less light is being transmitted. Bright red lens coatings lose light transmission equal to their reflective brightness. Further more, the red-end of the spectrum is information rich, unlike the blue-end that can be polluted with violet/ultra violet haze, which carries little or no information. A good quality lens should look dark and have a faint blue/blue green sheen, thus reflecting away information poor blue light.

Phase correction coatings

In binoculars with roof prisms the light path is split in two paths that reflect on either side of the roof prism ridge. One half of the light reflects from roof surface 1 to roof surface 2. The other half of the light reflects from roof surface 2 to roof surface 1. This causes the light to becomes partially polarized (due to a phenomenon called Brewster's angle). During subsequent reflections the direction of this polarization vector is changed but it is changed differently for each path in a manner similar to a Foucault pendulum. When the light following the two paths are recombined the polarization vectors of each path do not coincide. The angle between the two polarization vectors is called the phase shift, or the geometric phase, or the Berry phase. This interference between the two paths with different geometric phase results in a varying intensity distribution in the image reducing apparent contrast and resolution compared to a porro prism erecting system.[13] These unwanted interference effects can be suppressed by vapour depositing a special dielectric coating known as a phase-correction coating or P-coating on the roof surfaces of the roof prism. This coating corrects for the difference in geometric phase between the two paths so both have effectively the same phase shift and no interference degrades the image.

Binoculars using either a Schmidt-Pechan roof prism or an Abbe-Koenig roof prism benefit from phase coatings. Porro prism binoculars do not recombine beams after following two paths with different phase and so do not benefit from a phase coating.

Metallic mirror coatings

In binoculars with Schmidt-Pechan roof prisms, mirror coatings are added to some surfaces of the roof prism because the light is incident at one of the prism's glass-air boundaries at an angle less than the critical angle so total internal reflection does not occur. Without a mirror coating most of that light would be lost. Schmidt-Pechan roof prism use aluminium mirror coating (reflectivity of 87% to 93%) or silver mirror coating (reflectivity of 95% to 98%) is used.

In older designs silver mirror coatings were used but these coatings oxidized and lost reflectivity over time in unsealed binoculars. Aluminium mirror coatings were used in later unsealed designs because it did not tarnish even though it has a lower reflectivity than silver. Modern designs use either aluminium or silver. Silver is used in modern high-quality designs which are sealed and filled with a nitrogen or argon inert atmosphere so the silver mirror coating doesn't tarnish.[14]

Porro prism binoculars and roof prism binoculars using the Abbe-Koenig roof prism typically do not use mirror coatings because these prisms reflect with 100% reflectivity using total internal reflection in the prism.

Dielectric mirror coatings

Dielectric coatings are used in Schmidt-Pechan roof prism to cause the prism surfaces to act as a dielectric mirror. The non-metallic dielectric reflective coating is formed from several multilayers of alternating high and low refractive index materials deposited on the roof prism's reflective surfaces. Each single multilayer reflects a narrow band of light frequencies so several multilayers, each tuned to a different color, are required to reflect white light. This multi-multilayer coating increases reflectivity from the prism surfaces by acting as a distributed Bragg reflector. A well-designed dielectric coating can provide a reflectivity of more than 99% across the visible light spectrum. This reflectivity is much improved compared to either an aluminium mirror coating (87% to 93%) or silver mirror coating (95% to 98%).

Porro prism binoculars and roof prism binoculars using the Abbe-Koenig roof prism do not use dielectric coatings because these prisms reflect with very high reflectivity using total internal reflection in the prism rather than requiring a mirror coating.

Terms used to describe coatings

- for all binoculars

The presence of any coatings is typically denoted on binoculars by the following terms:

- coated optics: one or more surfaces are anti-reflective coated with a single-layer coating.

- fully coated: all air-to-glass surfaces are anti-reflective coated with a single-layer coating. Plastic lenses, however, if used, may not be coated.

- multi-coated: one or more surfaces have anti-reflective multi-layer coatings.

- fully multi-coated: all air-to-glass surfaces are anti-reflective multi-layer coated.

- for binoculars with roof prisms only (not needed for Porro prisms)

- phase-coated or P-coating: the roof prism has a phase-correcting coating

- aluminium-coated: the roof prism mirrors are coated with an aluminium coating. The default if a mirror coating isn't mentioned.

- silver-coated: the roof prism mirrors are coated with a silver coating

- dielectric-coated: the roof prism mirrors are coated with a dielectric coating

Applications

General use

Hand-held binoculars range from small 3 × 10 Galilean opera glasses, used in theaters, to glasses with 7 to 12 diameters magnification and 30 to 50 mm objectives for typical outdoor use.

Many tourist attractions have installed pedestal-mounted, coin-operated binoculars to allow visitors to obtain a closer view of the attraction. In the United Kingdom, 20 pence often gives a couple of minutes of operation, and in the United States, one or two quarters gives between one-and-a-half to two-and-a-half minutes.

Range finding

Many binoculars have range finding reticle (scale) superimposed upon the view. This scale allows the distance to the object to be estimated if the objects height is known (or estimable). The common mariner 7×50 binoculars have these scales with the angle between marks equal to 5 mil.[15] One mil is equivalent to the angle between the top and bottom of an object one meter in height at a distance of 1000 meters.

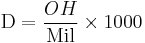

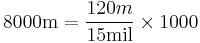

Therefore to estimate the distance to an object that is a known height the formula is:

where:

is the Distance to the object in meters.

is the Distance to the object in meters. is the known Object Height.

is the known Object Height. is the height of the object in number of Mil.

is the height of the object in number of Mil.

With the typical 5 mil scale (each mark is 5 mil), a lighthouse that is 3 marks high that is known to be 120 meters tall is 8000 meters distance.

Military

Binoculars have a long history of military use. Galilean designs were widely used up to the end of the 19th century when they gave way to porro prism types. Binoculars constructed for general military use tend to be more rugged than their civilian counterparts. They generally avoid fragile center focus arrangements in favor of independent focus, which also makes for easier, more effective weatherproofing. Prism sets in military binoculars may have redundant aluminized coatings on their prism sets to guarantee they don't lose their reflective qualities if they get wet.

One variant form was called "trench binoculars", a combination of binoculars and periscope, often used for artillery spotting purposes. It projected only a few inches above the parapet, thus keeping the viewer's head safely in the trench.

Military binoculars of the Cold War era were sometimes fitted with passive sensors that detected active IR emissions, while modern ones usually are fitted with filters blocking laser beams used as weapons. Further, binoculars designed for military usage may include a stadiametric reticle in one ocular in order to facilitate range estimation.

There are binoculars designed specifically for civilian and military use at sea. Hand held models will be 5× to 7× but with very large prism sets combined with eyepieces designed to give generous eye relief. This optical combination prevents the image vignetting or going dark when the binoculars are pitching and vibrating relative to the viewer's eye. Large, high-magnification models with large objectives are also used in fixed mountings.

Very large binocular naval rangefinders (up to 15 meters separation of the two objective lenses, weight 10 tons, for ranging World War II naval gun targets 25 km away) have been used, although late-20th century technology made this application redundant.

Astronomical

Binoculars are widely used by amateur astronomers; their wide field of view makes them useful for comet and supernova seeking (giant binoculars) and general observation (portable binoculars). Some binoculars in the 70 mm and larger range remain useful for terrestrial viewing; true astronomical binocular designs (often 90 mm and larger) typically dispense with prisms for correct image terrestrial viewing in order to maximize light transmission. Such binoculars also have removable eyepieces to vary magnification and are typically not designed to be waterproof or withstand rough field use.

A number of solar system objects that are mostly to completely invisible to the human eye are reasonably detectable with medium-size binoculars, including larger craters on the Moon; the dim outer planets Uranus and Neptune; the inner "minor planets" Ceres, Vesta and Pallas; Saturn's largest moon Titan; and the Galilean moons of Jupiter. Although visible unaided in pollution-free skies, Uranus and Vesta require binoculars for easy detection. 10×50 binoculars are limited to an apparent magnitude of +9.5 to +11 depending on sky conditions and observer experience.[16] Asteroids like Interamnia, Davida, Europa and, unless under exceptional conditions Hygiea, are too faint to be seen with commonly sold binoculars. Likewise too faint to be seen with most binoculars are the planetary moons except the Galileans and Titan, and the dwarf planets Pluto and Eris. Binoculars can show a few of the wider-split Binary star such as Albireo in the constellation Cygnus. Among deep sky objects, open clusters can be magnificent, such as the bright double cluster (NGC 869 and NGC 884) in the constellation Perseus, and globular clusters, such as M13 in Hercules, are easy to spot. Among nebulae, M17 in Sagittarius and the North American nebula (NGC 7000) in Cygnus are also readily viewed.

More difficult binocular targets include the phases of Venus and the rings of Saturn. Only binoculars with very high magnification, as in 20x or higher, are capable of discerning Saturn's rings to a recognizable extent. High-power binoculars can sometimes show one or two cloud belts on the disk of Jupiter if optics and observing conditions are sufficiently good. As a general rule, though, binoculars are not suitable for observing the surfaces of planets.

Of particular relevance for low-light and astronomical viewing is the ratio between magnifying power and objective lens diameter. A lower magnification facilitates a larger field of view which is useful in viewing large deep sky objects such as the Milky Way, nebulae, and galaxies, though the large (typically 7 mm) exit pupil means some of the gathered light is not used by older observers, as past age 50 most eyes' pupils rarely dilate over 5 mm wide. The large exit pupil will also image the night sky background, effectively decreasing contrast, making the detection of faint objects more difficult except perhaps in remote locations with negligible light pollution. Binoculars geared towards astronomical uses provide the most satisfying views with larger aperture objectives (in the 70 mm or 80 mm range). Astronomy binoculars typically have magnifications of 12.5 and greater. Many of the objects in the Messier Catalog and other objects of eighth magnitude and brighter are readily viewed in hand-held binoculars in the 35 to 40 mm range, such as are found in many households for birding, hunting, and viewing sports events. However larger binocular objectives are preferred for astronomy because the diameter of the objective lens regulates the total amount of light captured, and therefore determines the faintest star that can be observed. Due to their high magnification and heavy weight, these binoculars usually require some sort of mount to stabilize the image. A magnification of ten (10×) is usually considered the most that can be held comfortably steady without a tripod or other mount. Much larger binoculars have been made by amateur telescope makers, essentially using two refracting or reflecting astronomical telescopes, with mixed results.

List of binocular manufacturers

There are many companies that manufacturer binoculars, both past and present. They include:

- Barr and Stroud (UK) — sold binoculars commercially and primary supplier to the Royal Navy in WWII. The new range of Barr & Stroud binoculars are currently made in China (Nov. 2011) and distributed by Optical Vision Ltd.

- Bausch & Lomb (USA) — has not made binoculars since 1976, when they licensed their name to Bushnell, Inc., who made binoculars under the Bausch & Lomb name until the license expired, and was not renewed, in 2005.

- Bresser (Germany)

- Bushnell Corporation (USA)

- Canon Inc (Japan) — I.S. series: porro variants?

- Celestron

- DOCTER (optics) (Germany) - Nobilem series (Porro prisms)

- Fujinon (Japan) — FMTSX, FMTSX-2, MTSX series: porro.

- I.O.R. (Romania)

- Kamakura Koki Co., Ltd. - Large original equipment manufacturer manufacturer with factories in Japan and in China for companies such as Bushnell, Alpen, Zen Ray, Eagle Optics, Leupold & Stevens, Vixen [17]

- Leica Camera (Germany) — Ultravid, Duovid, Geovid, Trinovid: all are roof prism.

- Leupold & Stevens, Inc (USA)

- Meade Instruments (USA)– Glacier (roof prism), TravelView (porro), CaptureView (folding roof prism) and Astro Series (roof prism). Also sells under the name Coronado.

- Meopta (Czech Republic) — Meostar B1 (roof prism).

- Minox

- Nikon (Japan) — EDG Series, High Grade series, Monarch series, RAII, Spotter series: roof prism; Prostar series, Superior E series, E series, Action EX series: porro.

- Olympus Corporation (Japan)

- Pentax (Japan) — DCFED/SP/XP series: roof prism; UCF series: inverted porro; PCFV/WP/XCF series: porro.

- Steiner (Germany) [18]

- Sunagor (Japan)

- Swarovski Optik[19]

- Vixen (telescopes) (Japan) — Apex/Apex Pro: roof prism; Ultima: porro.

- Vivitar (USA)

- Vortex Optics (USA)

- Yukon Optics (Worldwide)

- Zeiss (Germany) — FL, Victory, Conquest: roof prism; 7×50 BGAT/T porro, 15×60 BGA/T porro, discontinued.

See also

- Anti-fog

- Binoviewer

- Globe effect

- Lens (optics)

- List of telescope types

- Monocular

- Optical telescope

- Spotting scope

- Tower viewer

References

- ^ a b Europa.com — The Early History of the Binocular

- ^ "groups.google.co.ke". groups.google.co.ke. http://groups.google.co.ke/group/sci.astro.amateur/tree/browse_frm/month/2002-08/5a0a50e6887feb69?rnum=71&_done=%2Fgroup%2Fsci.astro.amateur%2Fbrowse_frm%2Fmonth%2F2002-08%3F. Retrieved 2009-11-03.

- ^ photodigital.net — rec.photo.equipment.misc Discussion: Achille Victor Emile Daubresse, forgotten prism inventor

- ^ '''Astronomy Hacks''' By Robert Bruce Thompson, Barbara Fritchman Thompson, chapter 1, page 34. http://books.google.com/books?id=piwP9HXtpvUC&pg=PA34&lpg=PA34&dq=%22porro+prism%22+binoculars+produce+brighter+image+than+%22roof+prism%22#PPA34,M1. Retrieved 2009-11-03.

- ^ "Introduction to Optics 2nd ed"., pp.141-142, Pedrotti & Pedrotti, Prentice-Hall 1993

- ^ Johan Marais, Sasol Owls & Owling in South Africa, page 11

- ^ Pete Dunne, Pete Dunne on bird watching: the how-to, where-to, and when-to of birding, page 54

- ^ Philip S. Harrington, Star Ware: The Amateur Astronomer's Guide to Choosing, Buying, and Using, page 54

- ^ Stephen F. Tonkin, Binocular astronomy, page 46

- ^ thebinocularsite.com —A Parent's Guide to Choosing Binoculars for Children

- ^ Stephen Mensing, Star gazing through binoculars: a complete guide to binocular astronomy, page 32

- ^ Robert Bruce Thompson, Barbara Fritchman Thompson, Astronomy hacks, page 35

- ^ http://www.zbirding.info/zbirders/blogs/sing/archive/2006/08/09/189.aspx

- ^ "www.zbirding.info". www.zbirding.info. http://www.zbirding.info/Truth/prisms/prisms.htm. Retrieved 2009-11-03.

- ^ Binoculars.com — Marine 7 × 50 Binoculars. Bushnell

- ^ Ed Zarenski (2004). "Limiting Magnitude in Binoculars". Cloudy Nights. http://www.cloudynights.com/documents/limiting.pdf. Retrieved 2011-05-06.

- ^ panjiva.com - Limited Company Profile Kamakura Koki Co., Ltd. Supplier — Japan

- ^ "www.steiner-binoculars.com". http://www.steiner-binoculars.com/index.html. Retrieved 2009-12-21.

- ^ "www.regionhall.at —The Swarovski story". Regionhall.at. http://www.regionhall.at/en/the-swarovski-story.html. Retrieved 2009-11-03.

External links

- A Guide to Binoculars by Emil Neata

- The history of the telescope & the binocular by Peter Abrahams, May 2002